park springs

by Zoey Laird

In the foyer of the grand dining room, where seniors order salmon under chandeliers, monarch caterpillars eat and climb in a netted cage. We are encouraged to observe them there, in captivity, moving towards their inevitable metamorphosis. I wonder if they’ll be able to make their epic migration after being released, having been so long outside of their natural environment. I wonder if, like the monarchs, it’s too late for me. I’m almost thirty. I work in the senior living community where my maternal grandmother “Meme” lives.

Martha tears into the middle of the hallway naked, screaming, “Thief! Thief!” A nurse is washing her clothes but Martha won’t have it. She throws her cup of water across her bedroom. We must explain that she’s not being stolen from, and it’s time to get dressed for breakfast. I admire Martha, in all her blazing fury. She is one of the oldest and most active residents on the memory loss hall, scooting herself around in a wheelchair with both feet, somewhat resembling a crustacean, one eye pinched and oozing, a bloody growth on her cheek. Her southern drawl gives everything she says the air of a porch confessional. “How are you Martha?” More often than not, “Oh, horrible,” and yet she forgets being horrible easily and is ready to laugh, showing her missing, yellowed teeth. Martha sleeps underneath a trifecta of framed women. Herself and her mother in high school flank a gigantic portrait of a more distant female relative. This nameless woman, the story goes, burned to death in her own dress, “poor thing,” Martha says. “Her daddy couldn’t save her.” Why would this relative and her gruesome demise be so centrally placed above Martha’s bed? I like to think that Martha’s also burning - in that “fight the dying of the light” poetic sensibility. She draws near to the piano when someone’s playing, she laps the outside yard every day the sun is shining, and she plays hanky-panky with her handsome neighbor (he is well preserved but more addled than she).

I am an activities coordinator, and this facility is upper echelon - to end up here, one must have good solid family, or personal finances, or both. I started the job after Meme moved into an independent living apartment, across the street from the “skilled nursing” building. Meme has an Alzheimers diagnosis and it is likely that someday she will live here, probably after Martha is gone. Who knows? She could be in this very room.

Imagine Meme, who is small and sweet-natured, laying here in Martha’s fumes. Meme has no stories about distant, burning relatives - she recounts her happy childhood in Shreveport, Louisiana, where she married and built a house with her husband, the house I lived in for my first few years. Meme embodies my foundational sense of home, in part because we moved away, and that house was sold. I love her a lot. I sometimes wish she would rage like Martha. Her husband died in his fifties and she never had another lover (that I know of). I never knew my grandpas, so if I had to adopt one, Bob seems like a good choice.

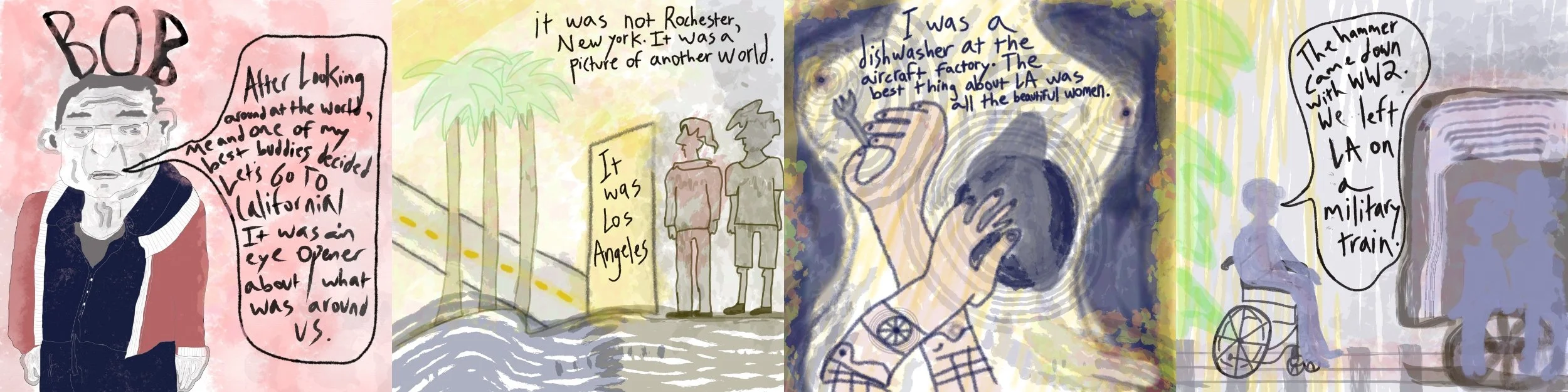

Bob’s ears stick out on either side of his head. He flirts in that tremulous, staring-eyes old man way, and stops himself because of his wife, he says, but she’s dead. He laughs at the funny pages and still reads books. Bob is what they call a “good guy.” Whatever defines “good guy-ness,” Bob’s got it. Bob will be overcome with some sentimental feeling, and his eyes fill, and his voice shakes. We throw a beach ball back and forth in a circle, and when it’s Bob’s turn he says he’s grateful for this big thing we’re in, together, and I think he means life. In the time I know Bob, he goes from standing with a walker to wheelchair-bound - this is what the nurses call “decline.” He tells me about a trip he took as a young man, from his hometown of Rochester, New York, to Los Angeles California, with his best friend. The key aspect of the trip was whim. They did it because they wanted to, and that’s all. I think about driving across the country to California. I wonder if I could be as ready to embrace whatever happens as nineteen year old Bob.

I’m ten years older than Bob was then, and I’ve already wandered around quite a bit. I feel lost, maybe it’s a late-onset quarter life crisis, or maybe this is he crux of turning thirty. I sleep on Meme’s couch when I’m working weekends, and the place feels like a “cruise ship in space.” There is a grand ballroom where people take their meals, and most of the wait staff are POC. It is discomfiting to watch elderly white people in a “privilege playground,” sending dinner back to the kitchen when it’s too dry, until their dying day. Meme wants to eat in the ballroom and I say no, can’t we just stay in your apartment? She is joining clubs and events and doing her best to adjust to her new home - while I cling to her, in a way that is, perhaps, regressive. I walk endlessly in the golf course, and one night, I end up on a treadmill in the gym (I have employee access). I am listening to a podcast about San Francisco in the heyday of hippiedom, and this treadmill has a simulation feature, that shows me the Filbert Steps, that famous hippie landmark. It’s as if I’m walking through San Francisco, on the senior’s treadmill. I decide to go.

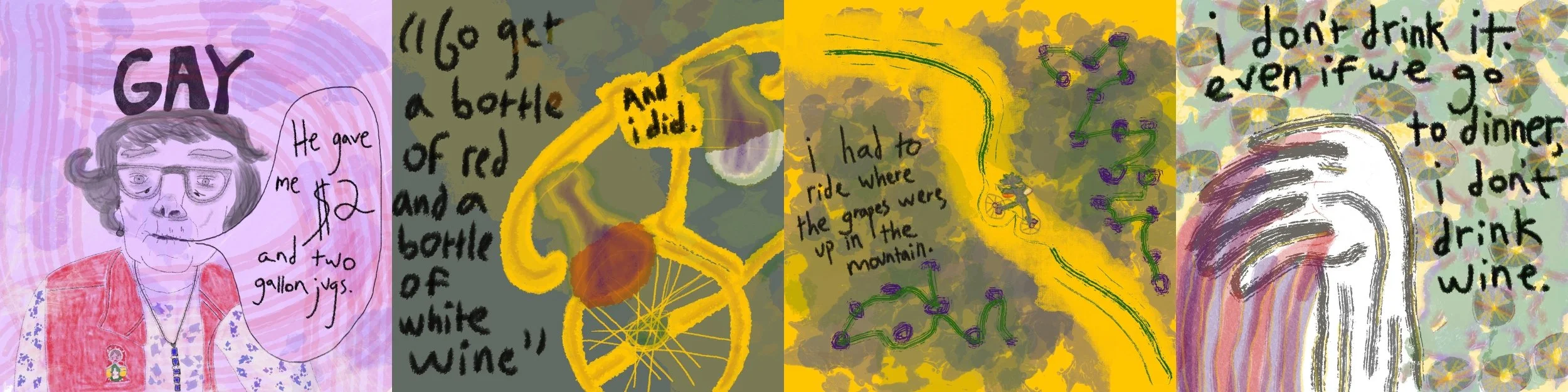

Gay is from California and she says San Francisco was named after her great-uncle. I stare at a painted wood rendering of the state map on her wall. She remembers her alcoholic father, who was as handsome as her mother was beautiful, sending her out to fill empty wine jugs, on her bike. Her husband Fred recently died, across the hall from her, after hitting his head. Fred also had an alcohol problem, Gay said. She doesn’t drink, but she’s ribald; when the confused neighbor guy wanders into her room looking for action (Martha’s ex-lover), Gay threatens to cut his dick off. Age does something to reveal beauty, sometimes, that works on Gay. Gay’s mother called her ugly, but Gay is a vision in her chunky jewelry, brightly colored clothing, sat on the bed amongst so many stuffed animals. She couldn’t have kids, so she adopted, and traveled all over the world with Fred, and working a lot of jobs of her own volition. When I visit her room, she asks what I’ve got planned for activities. “Something silly,” I say. Gay gives a wry laugh, “It all is.”

Meme takes me to the end of the pier, over the artificial lake with the geyser water feature. We are going to feed the turtles cat food, leftovers that her cat rejected. Absurdly, the turtles love the cat treats more than turtle food. The elderly gentleman next to us at the pier feeds them whole dog biscuits, which they also go crazy for, taking them in their beaks whole. Meme is 82. Time with her is precious, and I am certain that my decision to leave is selfish. I am also certain that I am in need of transformation, like the monarch caterpillars in the foyer. A few residents are excitedly gathered around the cage - there is a chrysalis hanging from the top. No butterflies emerged yet. I pull away from Meme’s apartment building on my 29th birthday. I take the old Toyota she bequeathed me, and drive across the country, to California, without a plan, really.

Christmas 2025, I’m seated at an old woman’s dinner table in her home on the famous Filbert Steps. She says in her last few years, she wants to focus on what she has left, rather than everything that’s happened. I vie for a place to sleep in her home, in exchange for help around the house, and there’s the irony - I came all this way, from the senior home treadmill, to San Francisco, and will resume my work with the elderly. She maintains the step’s gardens and she feeds the raccoons that arrive on her back patio, just like Meme and the turtles. I miss Meme, but I try not to despair - to see butterflies as a sign that I’m being led, at least to the inevitable story’s end, like Gay, and Bob, and Martha. They fly around here before their winter migration to Mexico, and congregate in the eucalyptus groves in Sacramento. We crane our necks upwards to watch them, from our flightless, meandering paths. I think about turning around and going home again, but why? On the bus back from Christmas dinner, I drunkenly tell a young man that “it all goes by so fast,” and I guess that’s all I know for sure.

Zoey Laird was raised in Atlanta and loves their grandmother, meme.